Motorized joystick for power wheelchair

design, course (MIT)

Overview

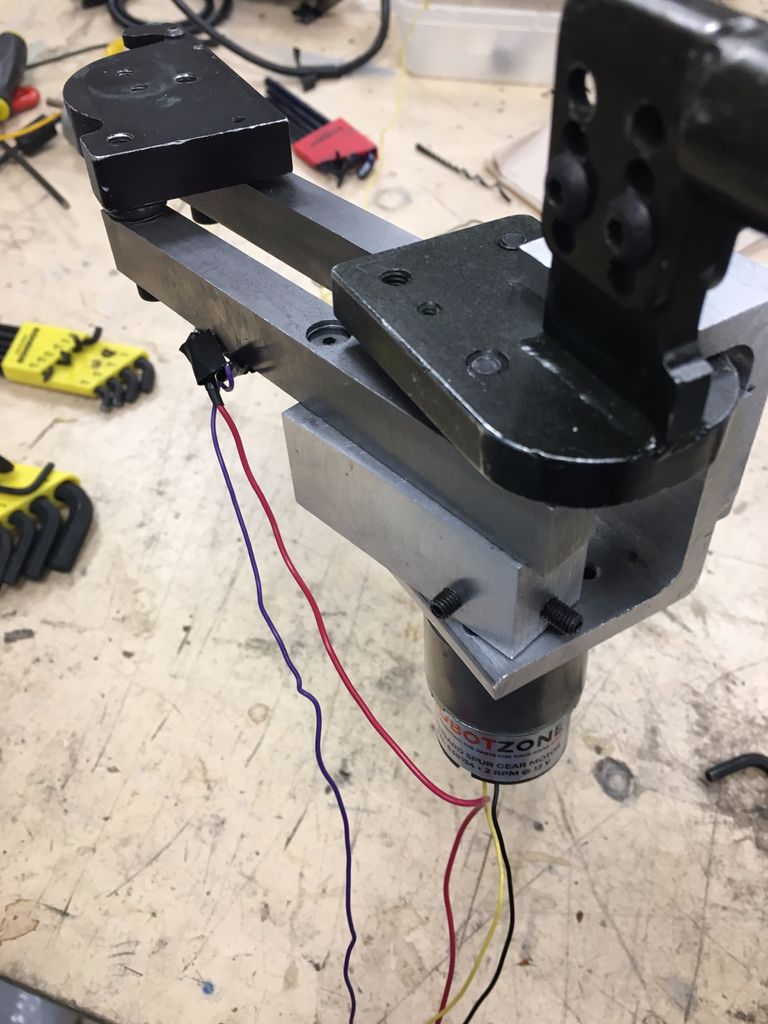

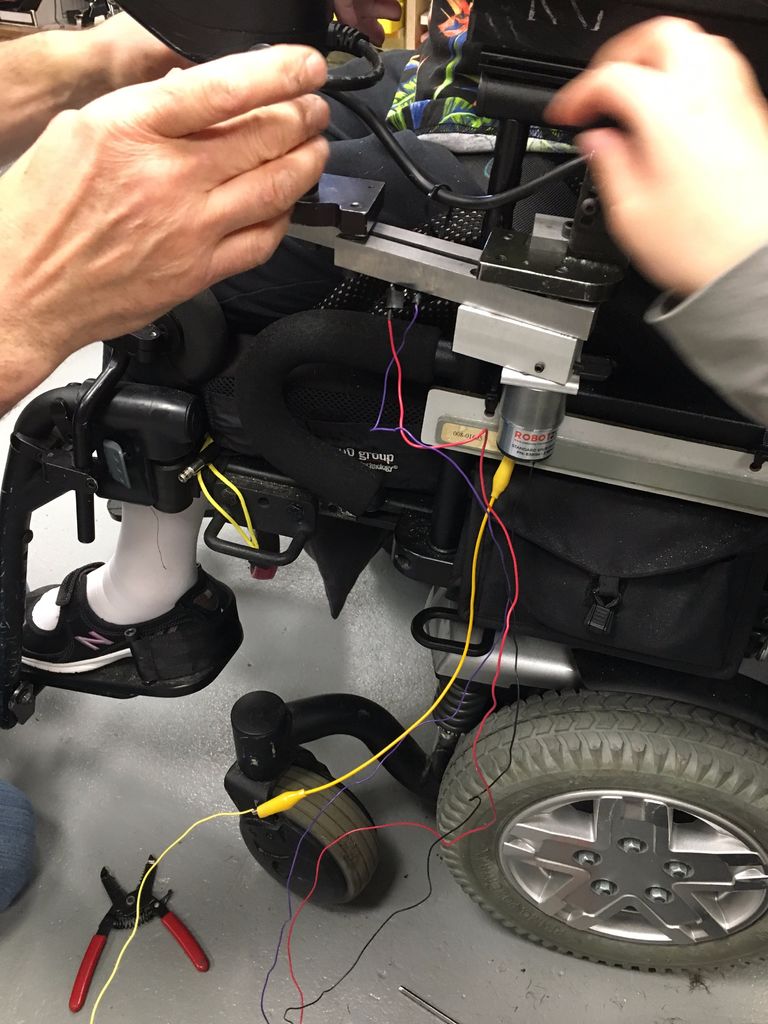

My Role: Interviewing/observing Rhonda initially and testing with her, designing and manufacturing the mechanical attachments that interfaced between the motor and Rhonda’s joystick arm

Tools/Skills: User Interviews, User Testing, Motor Selection, Machining

Timeline: September - May 2019 (8 months)

Team: 4 (MechE, EE)

Context

Multiple sclerosis can cause loss of strength in the arms. For power wheelchair users, the joystick juts out in front to allow easy access and control. However, it can get in the way when trying to reach a sink or a table. In this case, the user has to manually swing the joystick back, which can cause discomfort or in some cases, is not possible without assistance. A previous solution to this problem was developed in the past in this class, but it lacked robustness, was not easy to debug the electronics, and could not be adapted for another user with even slightly different needs (our user was left-handed rather than right-handed).

Goal

Create an improved attachment to motorize the retracting of the joystick for a power wheelchair that can be adapted to various users

Outcomes

1) Developed an improved mechanism to motorize joystick retraction on a power wheelchair

2) Modified the prototype to account for varying loads

3) Installed the prototype on Rhonda’s wheelchair for use

4) Documented the initial version and the modified version in detail in this Instructable which was featured on the website

Design Process

After meeting with Rhonda, our user, several times, we developed a first prototype. This process is shown in the video below.

However, we found that after building it in the shop, when we tested it with Rhonda, it was not reliable. When attached to her wheelchair, the load on the motor was much higher than what we had initially accounted for. The joystick arm was deflecting due to the load of the joystick at the end, increasing the load on the motor beyond what it was able to handle. For this reason, we iterated on the design another time. First, we replaced the motor with a more powerful motor, though we had to trade-off the speed of retraction. Then, we replaced the aluminum bars of the arm with thinner, but taller bars to prevent the deflection. Finally, we made the bars out of steel, as we found that it improved the robustness of the attachment, despite being slightly heavier.

Reflection

There were many lessons learned from this project (developed as part of 2.78, Principles and Practices of Assistive Technology), particularly about how a theoretical design and the design in reality may not match up. Despite having access to a test wheelchair arm and specifying a motor with a safety factor, we found that our motor could not handle the load and friction that was present in reality on Rhonda’s wheelchair. Thus, we were forced to make our device operate more slowly so that it would operate at all. I learned how translating a design into its actual operating conditions can shed light on unforeseen problems and on the trade-offs that often need to be made when designing for performance. Performing frequent testing under the operating environment was impossible because it would disturb Rhonda’s daily life, but it likely would have helped if we had planned ahead and created a few design variations to make the most of our occasional testing sessions and discover the problems upfront.