Design space exploration in VR

design, research

Overview

My Role: Contributions both as a researcher and developer: generating the designs and creating the pipeline to transfer them between the 3D modeling software and the VR application, creating the VR environments, setting up the data logging for the user study, designing the user study, administering the user study, analyzing the quantitative and qualitative behavioral data

Tools/Skills: User Study, Unity, Rhino3D/Grasshopper, C#, Python

Timeline: August 2021 - December 2022 (17 months)

Team: 5 (MechE, Design, HCI)

Context

Virtual reality enables the creation of realistic environments and the ability to use spatial senses rather than only rely on vision. There is the possibility to use VR tools in a design context, but it is important to avoid simply porting existing workflows into VR without leveraging its unique benefits. Decisions related to designing or purchasing physical objects may benefit from the interactions afforded by VR because it is difficult to convey many aspects of a 3D, physical object using screen-based interfaces.

Goal

- Prototype interactions that leverage unique aspects of VR to explore a large-scale design space

- Evaluate the utility of VR for such a task in comparison to screen-based interfaces

Outcomes

1) Developed interactions that allowed users to narrow down from a space of over 3000 options to a final option in a short amount of time (~15 minutes)

2) Evaluated the interactions for their usability, finding that they were generally intuitive, except for the functionality-based approach which users had a hard time understanding and would require more training or a paradigm shift in approach

3) Evaluated the interface modality (screen-based and VR), finding that certain aspects of search and exploration are better suited for one interface type over the other

4) Identified potential future directions

Developing the interactions

We used the example of furniture (storage shelving) to demonstrate different interactions that can allow users to better search through a design space.

We developed 2 primary interactions:

1) A direct manipulation filter that allows users to specify the geometry of their preferred design, using a virtual environment to reference scale

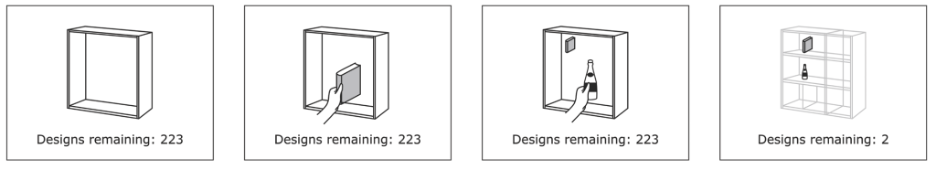

2) A functionality filter that allows users to sort through designs based on the ability of the shelf to hold their desired items

The video below shows the initial version of our interactions, which were presented at CHI 2022 as Late Breaking Work:

Iterating on the interactions

Based on pilot testing of people using the interactions, we improved the interactions and added a few additional features that could be evaluated in a user study.

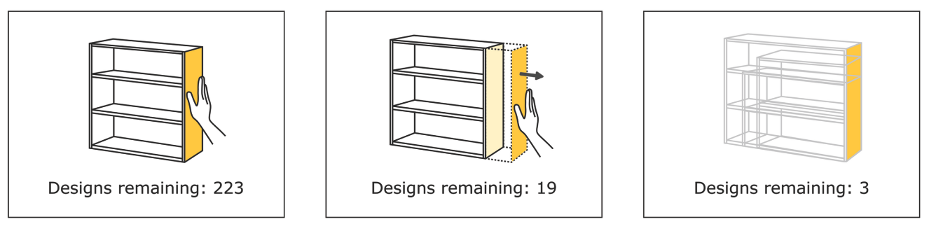

1) Users could originally visually filter down by seeing the overlay of transparent shelves that represented the design space and then had to look elsewhere to see the number of designs remaining after filtering. Having easier access to the exact number could help people set their filters more precisely so that they would not over-constrain the space too soon. Placing the number as a tag on the tool and updating it in real-time allowed users to get an at-glance summary of the impact of their actions on the resulting design space.

2) Users originally made their decisions in an empty virtual environment. However, adding a room environment that could simulate how the design would be used in-context was beneficial for further utilizing the spatial benefits of VR. Then, users could place the shelf in the room and walk around to see how it would be used within an actual space.

3) Users were embodied as themselves when entering the VR environment. However, another benefit of VR is the ability to change embodiment. In order to facilitate design from other perspectives, we added a small feature that allowed users to modify their height (taller or shorter) to better explore how the shelves might be used by people different from themselves.

Using those insights, the interactions were refined and then used in a user study (presented at ICED ‘23 and published). An example of using the refined interactions to narrow down to a desired design is shwon below:

Skip to Timestamp 01:39 - 02:29 for a demonstration of the Direct Manipulation Filter, which allows gestural specification of geometry

Skip to Timestamp 04:43 - 05:24 for a demonstration of the Functionality Filter, which allows the placement of objects to specify how the design will function (how the shelf will hold items)

Skip to Timestamp 5:45 - 7:00 for a demonstration of using both the Direct Manipulation Filter and Functionality Filter to constrain the design space based on both form and function

User study - quantitative and qualitative evaluation

In order to evaluate the interactions and the interface modality, we developed 2 tasks for participants (N=28, each having at least a little design experience) to complete. Participants were given two design tasks: select a shelf to display projects in a Design Institute’s entry and select a shelf for a small library in the lobby. All participants completed the two tasks in the same order, but either completed the first task using VR or a screen-based version of the interface with the same interactions (adapted slightly so they wouldn’t be disadvantaged completely by the modality). The order in which the interfaces were used was assigned randomly.

We provided training on how to use each interface before allowing participants to complete each task. We collected action logs of what participants did, survey responses after each task, and an overall post-study survey.

Key insights and impact

1. Logs reveal differences in use of functionality interaction

Logs of when people used the interactions during the task revealed that some people used the interactions as expected and some people did not. For example, the functionality filter was originally developed so that users could specify high-level abstractions of function first, rather than low-level design parameters. Two broad types of users emerged for this interaction:

“Function first”: Used the functionality filter at the start to narrow design space to fewer, but visually diverse possibilities

“Function checker”: Increased their use of the functionality filter at the end, often after a final design had been selected (e.g., to check if objects could be placed as desired)

2. Expressing function-based intent directly is challenging, but an immersive interface may help

Furthermore, the use of the functionality filter revealed where there the interactions are influenced by different interface modalities. While the direct manipulation filters were rated similarly for usefulness across both screen-based and VR modalities, the functionality filter had slightly higher ratings of usefulness when it was used in the VR vs. screen-based interface. At the same time, overall reviews of the functionality filter was mixed - some people found it very useful and others found it not useful at all.

3. VR may not support breadth of exploration, but instead enable in-depth consideration of an option’s benefits and constraints (e.g., by sense of scale, simulating function)

Additionally, commenting on completing the task in the two different interface modalities overall, participants noted that the screen-based interface let them feel less limited in exploration:

“By being able to physically, or in this case, virtually, experience the designs in person gave it a greater sense of how a user would be interacting with the design constrain[ing] heavily the ranges of designs I could consider. With 2D, I didn’t feel like I was in the space and constrained, which allowed me to look at more designs…”

But the VR interface enabled them to understand the different alternatives and how they would be used better:

“Although it took a while to get used to the control, I was able to better imagine myself using the design and get a better sense of scale. There were times where I couldn’t reach the top of the shelve[s], and that helped me choose what height shelves I should use.”

These insights can be applied to guide decisions about which type of interface modality should be used for search and exploration tasks, both in and outside of design, as well as guide the development of top-down, intent-based expression, which can be challenging for users to conceptualize.

Next steps

While the novel interactions developed here provide insights into different ways to enable design space exploration, there were clearly some challenges. Overall, communicating to participants how the filters worked was challenging because designers are used to being able to create geometries from the bottom-up, rather than specify what they are looking for from the top-down. More work is required to understand how intent specification will change as designers and consumers alike use new types of tools to facilitate creation, search, and exploration. VR demonstrated potential for activating spatial considerations during decision making, but there are still few ways to precisely measure the impacts of such immersion on both experience and outcomes aside from self-reported measures. The action logs gave some insights into how interactions were being used, but a larger sample size is needed to make sense of patterns due to the large variability in what participants do in more open-ended (but more realistic) tasks.

Reflection

This was an interesting exploration of how we might want to specify constraints or requirements using modalities other than text. In this case, VR allows an immersive way to specify desired functionality or size, as well as view the designs from different perspectives. However, a challenge with using VR in the way we implemented the interactions is that you cannot see the design from a “bird’s eye view,” which is a convenience of traditional 3D software. In addition, people are not used to interacting with design spaces in this way (at a higher-level of abstraction, based on use and gestural specification of geometry) compared to modifications at a parameter level. Therefore, more work would have to be done to understand how people can create a better mental model such an approach and what capabilities it may enable. Furthermore, this project was done before the more widespread accessibility of text-to-3D models. The approach taken here might lead to interesting considerations of how designers or consumers can better specify what they are looking for when it is difficult to describe in words.

See the following publications for more details about this project:

GeneratiVR: Spatial Interactions in Virtual Reality to Explore Generative Design Spaces (CHI Extended Abstracts 2022)

VR or Not? Investigating Interface Type and User Strategies for Interactive Design Space Exploration (International Conference on Engineering Design 2023)